In December 1968 a plane carrying Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Carlos Fuentes touched down in Prague. The two authors had come to show solidarity with Czechoslovakia’s writers and to discuss the year’s historic events: how the hopes of Dubček’s Prague Spring had ebbed into the interminable autumn of the Soviet patriarch (totalitarian time ran slow, Solzhenitsyn had warned).

Their host was the Czech novelist and essayist Milan Kundera, who has died in Paris aged 94. Mindful of the need to talk freely, Kundera took his guests to a sauna, the one place in the city impossible to bug. As the steam rose and their bodies began to overheat, the visitors asked where they might sluice off the sweat. The Czech led them to a back door opening onto a hole in the frozen Vltava. He motioned towards the river and they clambered down, expecting him to follow. But Kundera remained on the bank, bellowing with laughter as these hothouse flowers of Latin-American literature emerged like popsicles from the icy waters of Mitteleuropa.

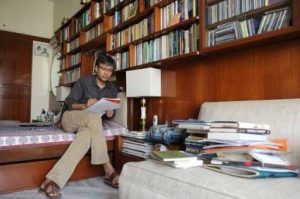

“The second Czech K” as Fuentes called him, was 39 in 1968 with a growing reputation as poet, dramatist, essayist and formidable intellectual. His first novel, The Joke (turned down initially for opposing official ideology), had finally been published the year before, gaining cult success, but this moment when socialism with a human face met the “threatening fists” of power was decisive, providing not just the setting for his best-known work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1982), but the governing theme of his oeuvre: how to be a novelist in an age when “political demagoguery has managed to ‘sentimentalize’ the will to power”. For Kundera, who once defined himself as “a hedonist trapped in a world politicised in the extreme”, and whose novels are replete with bodily pleasures and humiliations, the lyrical intoxication of poet and revolutionary were dangerously allied.

He was born in 1929 in the Moravian capital Brno, where his father, a pianist, composer and musicologist, was head of the Janáček Music Academy from 1948 to 1961. The son also studied composition, and while his father did not make a professional pianist of him, music was a lifelong love, often summoned in his novels and essays. At Prague’s Charles University, he studied literature and aesthetics and like most of his generation was caught up in postwar euphoria, attracted to the possibilities held out by communism, after the blight of nazism and collaboration, of a Czech society reborn. The Russians liberated the country in 1945 and no one was surprised when the following year the communist party won 38% of the vote and formed a coalition government. Kundera joined (“I too once danced in a ring. It was the Spring of 1948,” he confesses in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, 1979), and some of his poetry at this time displays the kind of lyrical enthusiasm he would later decry.

He switched his degree to film but in 1950 was expelled for “anti-party activities”, an incident that gave birth to The Joke. Allowed to return to his studies, he rejoined the political fold in 1956, remaining in the party for the next 14 years. His humour and freewheeling, speculative manner as a teacher of world literature at the Prague Film School influenced many Czech new wave directors, Milos Forman among them. But from the start, being funny was a serious business. In The Joke a man sends a postcard with the mock salutation, “Long Live Trotsky!” The irony is lost on the censors, the result disastrous. Similarly, the stories that make up Laughable Loves (1963-8), move in a blink from farce to horror: the book was completed three days before the Soviet invasion.

Like many artists and intellectuals he was involved in the movement to create a de-Stalinised socialism. At the Fourth Congress of the Writers’ Union in 1967, Kundera gave a rallying speech arguing that Czechoslovakia’s existential precariousness (frequently overrun, its language threatened) placed it in a unique position from which to address the 20th century, but this could be realised “only [in] conditions of total freedom”. However, after the invasion, and Dubček’s humiliation at Soviet hands, his belief in the possibility of change unravelled: he lost “the privilege to work”, his books were removed from libraries and, by 1970 and normalizace – the policy of undoing Dubček’s reforms and returning to the old standards – he could no longer publish.

His Kafkaesque view of power led to disagreements with the dissident playwright Václav Havel whom he attacked for encouraging the illusion of hope (“moral exhibitionism”) in a situation where history preordained defeat. Only apart from the fray could you record your testament and tip your hat: this is how the novel faces power, he argued famously, with “the fight of memory against forgetting”. Havel – who remained in “the country of the weak” (The Unbearable Lightness of Being), was imprisoned, then fought to lead a new Czech nation in the finally successful Velvet Revolution – admonished him: history is not a clever divinity playing jokes on us; we are “creators of our own fate”. But Kundera had long since left the stage.

At about the same time, in 1968, he started being translated abroad, a “traumatic” experience for him: he accused publishers in the west of acting like Moscow censors, when they, too, tried to “normalise” his work to fit Western standards. But he took a job in France at the University of Rennes, and four years later his Czech citizenship was revoked. He considerably revised into French all his works written in Czech, then set a novel in France, Immortality (1988), concerning the proliferation of the media’s “imagology”. Finally he began writing entirely in French (despite which, he won the 2007 Czech State Prize for Literature). His Gallic novels – Slowness (memory intensifies as speed reduces), Identity (1998), Ignorance (2000), and The Festival of Insignificance (2014) – were well-received though none had the impact of the earlier Czech works.

The Book Of Laughter and Forgetting, the first novel to come from his exile – essayistic, multi-storied, but with scenes so transparently born of argument as to be “almost hypothetical” (James Wood, The New Republic) – stages a battle between devilish anti-meaning and the angelic one true idea of communism. He pictures these celestial figures laughing in the face of one another, a murderous dialectic against which the writer, with his love of variety and inconclusiveness, has no defence: “the terrifying laughter of angels…covers my every word with its din.”

His writing contains much of this dark laughter, strewn with gags, pranks and paradoxes, and there are good reasons for this. He exploits the vein of black comedy that central European history gives its writers as a birthright, but more ambitiously (and Kundera is nothing if not ambitious) it is humour, originating in the laughter of Boccacio, Cervantes and Rabelais, that he sees underpinning the European novel, and which he argues, in four volumes of essays, has uniquely shaped modern western consciousness.

Octavio Paz thought “Humour… the great invention of the modern spirit”, and for Kundera no one better explored and disseminated this idea than Don Quixote’s children: those unheroic, self-deluding and body-bound creatures whose mortal comedy produces in the novel an art of essential ambiguity and polyphony. His defence of its mockery and refusal to judge (even as he senses its demise) is that springing from the novel’s pages comes no less than our understanding of what it is to be an individual, and with this, the idea of “human rights”.

All of which may seem a heavy load for any book to bear, and perhaps explains why some critics find his writing too didactic (“all talk and no story”), and find the weight of argument defensively deployed and insufficiently balanced by the lightness of touch required by comedy and eroticism. For all Kundera’s engaging intelligence, John Updike also felt a “strangeness that locks us out.” Unlike Marquez, or Rushdie – the company to which he aspired – there is no sign of the shaman, no risk of being thought a sham. Perhaps his refusal to fall for anything – neither politics’ nor poetry’s intoxications – his pedagogic desire to disabuse and disenchant, and his view of the novel as a supremely moral and rational art, leaves him, peculiarly, a novelist disinclined to enchant. For some though, like the novelist and essayist Geoff Dyer, Kundera’s importance lies precisely in this extension of the novel into meditative interrogation, by which, Dyer thinks, he “recalibrated fiction to create forms of new knowledge”.

In 2008, after an investigation conducted by Prague’s Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, an accusation was made against Kundera in the Czech magazine Respekt. It was claimed that in 1950 – the year he was expelled from the Party – Kundera gave the name of Miroslav Dvořáček to the police. Dvořáček, a pilot, had escaped from Czechoslovakia but returned as an intelligence agent for American anti-communists; he was subsequently arrested, only narrowly escaped the death penalty, and served 14 years in a labour camp. Kundera denied that he was the informant and a group of international writers including Fuentes, Garcia Marquez, Rushdie, Philip Roth, Orhan Pamuk, Nadine Gordimer and J.M Coetzee came swiftly to his defence in a letter declaring him the victim of “orchestrated slander”. Havel said he thought the way events unfolded too “stupid” for Kundera to have been involved, and that his old friend and adversary, who had scrupulously kept away from the media, rarely giving interviews, had “become entangled in a thoroughly Kunderaesque world, one that he has so masterly managed to keep at a distance from all his real life.”

The following year, Kundera published Encounter, a series of essays, some going back twenty years, in which he returns to “old themes…old loves”. In ‘What Will Be Left of You, Bertolt?’ he says that the love of art is dying in Europe. Now, rather than “the work itself”, attention is trained upon the life which has become the focus of a need to “ferret out Sin”, to uncover and defrock. (So, a new biography has Brecht abusing girlfriends, sympathising with Stalin, secretly homosexual and smelling badly). What began as the task of demystification in criticism has become a matter of accusation: Europe, he warns, is “moving into the age of the prosecutors.” The essays in Encounter seek to redress this by re-reading those who have been “misunderstood”, celebrating others unjustly neglected. In one, about Bohumil Hrabal, the wondrous author of Closely Observed Trains, Kundera reiterates his view of the relation of politics and art, and his belief in the pre-eminence of the novel in the struggle for human liberation: “One single book by Hrabal does more for people, for their freedom of mind, than all the rest of us with our actions, our gestures, our noisy protests!”

This obituary was published online by the Guardian on 12.5.2023, and in print on 13.5.2023.

To read Buchi Emecheta’s novel, The Joys of Motherhood (published by Allison and Busby in 1979, now republished in Penguin Modern Classics), is to be reminded how much work is still to be done exploring the global nature of the twentieth century’s two world wars, and their impact on populations who had no say in their beginning or ending, and little understanding of why they were conducted. Emecheta’s novel is set in Nigeria and traces the life of Nnu Ego who, having failed to produce a child, is forced out of her father’s traditional Ibo village to marry a stranger in Lagos. When she arrives in the capital in the mid-1930s, she finds herself in a busy, complex city where, under the rule of British colonists, old traditions are falling away, emasculating Nigerian men and clouding traditional gender roles.

Having grown up among powerful Ibo men who worked in the fields, when Nnu Ego first meets the man she is to marry in Lagos, she is repulsed by the sight of this “jelly of a man” who washes clothes for an English family. She winces as she watches Nnaife “hanging out the white woman’s smalls” or pretending not to hear when the “master” calls him a “baboon”. But these grievances seem as nothing after Nnu Ego’s longed-for first child dies suddenly, and then Nnaife’s employer returns to England to fight in the Second World War. With only two weeks’ notice, the family loses its income and home. Despite the strain on their marriage, the ill-matched couple survive these calamities: Nnu Ego sells cigarettes to passing commuters and Nnaife finds work as a grass-cutter on the railways. But just as they are beginning to find their feet again, and Nnu Ego at last experiences “the joys of motherhood” after giving birth to sons, Nnaife and several of his workmates are pressganged into the army and sent overseas to fight for the British in Burma. Hearing the news of Nnaife’s abduction, neighbours gather to sympathise. “Why can’t they fight their own wars? Why drag us innocent Africans into it”, one of them asks. “The British own us”, another replies, “just like God does, and just like God they are free to take any of us when they wish.”

In The Joys of Motherhood, this alarming sense of powerlessness, and the attempts to overcome it in hostile circumstances, is conveyed by Emecheta with an insightfulness born of experience. Although this is not an autobiographical work, details from Emecheta’s family life are sewn into the novel’s pages, helping to illuminate Nigeria’s painful transition from traditional patriarchy to colonial modernity. Like her father, a railway worker who died of a wound contracted while fighting for the British in Burma, Nnaife never really understands the central drama of his life: why he was shipped to Burma to fight what he had been told was a European war. In the same way, Nnu Ego’s existence echoes that of Emecheta’s mother who was sold into slavery as a young girl only escaping when her “mistress” died. In the ironically titled, The Joys of Motherhood, Nnu Ego is plagued by the spirit of a slave-girl who refuses to die with her mistress. And just as Emecheta’s mother had, Nnu Ego puts all her energy into working so she can afford to educate her sons, while keeping her daughters at home where they suffer from malnutrition. But this bargain does not pay off for Nnu Ego. Instead of supporting her in old age, the educated boys forget their mother when they emigrate to America and Canada, leaving her to die alone on a roadside. The family finally come together again to provide a magnificent funeral but despite this, when Nnu Ego’s offspring call upon her spirit to make them as fertile as she was, she does “not answer prayers for children.”

This review appeared in the TLS on 14th April 2023.

The years assayed in Selby Wynn Schwartz’s new novel, After Sappho, between 1885 and 1928, are perhaps for women in the West some of the most remarkable in our history. Towards the end of the nineteenth century the bicycle and typewriter were changing women’s lives, bringing freedom of movement and the possibility of skilled wage labour to millions who were previously corseted and – in the case of middle and upper class women – cosseted. Within forty years we were moving through cities in unprecedented number, driving automobiles and working heavy machinery during the war, dressing in loose-fitting garments and beginning to vote. How did this happen? It wasn’t just technology that drove the revolution in everyday life, transformed relations between the sexes, and fundamentally altered the way women looked at one another and understood themselves. Women, individually and collectively, fought to make this happen. “Power lies in the shadows”, Rebecca Solnit wrote recently, and Wynn Schwartz gathers a teeming cast of American and European women who broke out of marginal existences where they lived overshadowed by men, to seek the light.

After decades of feminist scrutiny of this history, Wynn Schwartz is just one of a group of writers, scholars and thinkers who are now asking us to reconsider the period, and in particular, the part that lesbians played in it. Among their books are No Modernism Without Lesbians (Head of Zeus, 2020) Diana Souhami’s recent biography of four key players in the development of modernism: Sylvia Beach, Bryher, Natalie Barney, and Gertrude Stein; Lesbian Modernism (Edinburgh University Press, 2019), Elizabeth English’s study of the narrative strategies that writers used to outwit censorship; and Susan S Lanser’s work on how lesbian literature shaped the modernist era (rather than the other way around) in The Sexuality of History: Modernity and the Sapphic (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

But in Wynn Schwartz’s seductive, elegiac and unclassifiable work (After Sappho is a fiction that contains a multitude of ‘real’ women) the case is made for lesbian pre-eminence in this era not only with the weight and detail of accumulated fact – she gives us biographical information, precis of misogynist laws and court cases brought against the “Cult of the Clitoris”, descriptions of books, bodies, paintings, buildings and furniture – but in the way her protagonists float through the narrative as her writing absorbs and articulates history’s more intangible flows. With great finesse, Wynn Schwartz conjures the feelings, atmospheres, influences, rumours and desires that emanated from these women and swirled around them. She creates a style akin to the optative in ancient Greek grammar, a mood of hovering uncertainty with which lesbians, she tells us, in the precariousness of their lives, were well-acquainted (“if only, if only…let it be so”).Wynn Schwartz also dramatizes those complex questions of identity and solidarity the women faced, elaborating the pathways of connection they built by studying, gathering, and, most mysterious of all, by “becoming”. What they found in Sappho’s poetry were “words we had crossed centuries to find”, words that proposed daring alternate ways of being, liberating them from the bonds of patriarchy. In After Sappho, Wynn Schwartz follows scores of these women who having encountered the poet’s words, abandoned their old lives and – like all good modernists – went in search of the new.

Why Sappho?

A classical education, Virginia Woolf observed in 1925 in her essay ‘On Not Knowing Greek’, is the bedrock of learning in the west, and, as the disgraced ex-Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, has been keen to remind us, it is also a badge of elitism and a weapon of rhetorical power. If state education is denied us, Woolf and others argued, it must be fought for. But alongside this we should seek out Sappho and the women who subsequently taught her work for ourselves. Threaded through After Sappho is the idea that for many women at this time, to become a lesbian meant a life of study and devotion, meant becoming an inveterate reader. A surprising number of Wynn Schwartz’s retinue turned themselves into autodidacts, making pilgrimages to Lesbos, teaching themselves Greek, and creating their own translations of ancient texts. Others, in a concerted act of overturning, rewrote classical histories and myths in the light of feminism. This project of remaking the classical world was in line with advice given by one Woolf’s lovers, Vita Sackville West: “The only revenge one could take on certain men was to brazenly rewrite them”. But besides redressing perceived injustices to women in stories written by men, this revisionary imagination was perhaps most pointedly applied to the story of Sappho’s death, which, some male scholars claimed, saw her committing suicide by flinging herself of a cliff for the love of a man.

The repeated act of looking back to Sappho lends Wynn Schwartz’s novel a mood of retrospection, a mood, she explains, that is expressed in Greek grammar as the genitive of remembering. Greek “is the language that has us most in bondage” Woolf wrote, “the desire for that which perpetually lures us back”. Part of the lure of Sappho’s poetry, of course, is that is comes down to us in pieces – something which has been attributed in part to the sexism of early male scholars who believed that, as a woman, her work was unworthy of preservation. Despite this, the portions we have of Sappho’s writing imbues in our contemporary appreciation of what remains of her work, and the little we know of her life, a sense of longing – for something that in its piecemeal state is forever in need of completion. This state of imperfection is mirrored throughout After Sappho in the struggle to “become” a lesbian, to find oneself in a denied and disregarded Sapphic tradition, and to imagine a future “Afterworld”, as Sappho called it, in which women might live and love freely.

The fragmentation of Sappho’s work also acts as an analogue for the fascination that many modernists had for Classicism. When turn-of-the-century archaeologists began uncovering the ruins of Ancient Greece, their discoveries excited the modernist imagination, encouraging writers and painters to look for new forms in very old ones, and influencing the apocalyptic aesthetic which found its way into the poetry of, among others, T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats (“These fragments I have shored against my ruins”/”somewhere in the sands of the desert”). The two movements also had in common a pared-back aesthetic, a belief in the centrality of art, and democratic impulses – until, in the case of modernism, these were hijacked in the 1920s by fascist populism, something to which a handful of Wynn Schwartz’s women were drawn.

Who are “We”?

Wynn Schwartz’s narration takes place in the plural first person and there are many elements to her collective “We” and “Us”. First it is affirmative of numbers, companionship and solidarity, a radical assertion of a common history and a mutual understanding of what “We” think about ourselves and the world at any one moment. As with the use of “We” in Annie Ernaux’s sweeping history of postwar France , The Years (Fitzcarraldo, 2018), Wynn Schwartz’s collective approach asks the reader to endlessly rethink the narrator’s identity as her fluid multiple narrator morphs in shape and meaning. Mostly in After Sappho, the “We” denotes a lesbian identity, but it also encompasses straight women engaged in the cause of female liberation, bisexual women, and transvestites – women who wanted to be male, or those who presented themselves as masculine in order to refuse the cramped space of femininity. There is even the occasional male, Oscar Wilde, or Isadora Duncan’s brother, Raymond, included within the elastic parameters of the story. And finally, towards the end of the novel, there is a Black woman, the dancer Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith, and Nathalie Barney’s servant, Berthe Cleyrergue (“she could cook, she could sew, she had intelligent green eyes”), gesturing towards the lives otherwise missing from this collective identity.

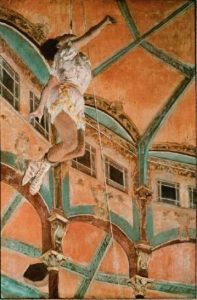

Within her broader narrative, Wynn Schwartz threads the stories of individual women and their amorous, friendly and sometimes fractious relations with one another. Some are well-known (Woolf, Colette, Gertrude Stein) others less familiar: much of the early part of the story relays the battles of Italian feminists, communists and lesbians against their country’s draconian laws. There are the women who acted as salonistas, teachers, leaders and icons (Nathalie Barney), and around these, acolytes and followers, a chorus giving voice to questions, rumours and praise songs. Others are activists demanding the vote, rights, and access to education; then there are artists of all kinds: writers and translators (Djuna Barnes, Renée Vivien, Sibilla Aleramo), painters (Romaine Brooks), designers such as Eileen Grey who wanted to reinvent everyday life and turn houses inside out, as well as actresses (Eleonora Duse, Sarah Bernhardt) and dancers (Liane de Pougy, Maud Allan, Eva Palmer-Sikelianos), some of whom who specialised in Greek song and culture, dressing in robes and making their own leather sandals. There are the “voyantes”, those Cassandras and Sibyls who imagined what most of us cannot, the lamplighters shining the way to possible futures in the Afterland. Finally, there is The Author herself, making the book into a collaboration between the past and the present, and proving by her words the vindication of posterity. In After Sappho, Wynn Schwartz draws lesbians out of anonymity and into history, ensuring that those who were ignored, excluded or denigrated will now and in the future be looked back upon as trailblazers. As Sappho predicted: “You may forget but let me tell you this: someone in some future time will think of us.”

What did “We” do and how did “We” do it?

It’s worth noting that one of the reasons for the freedoms gained by women in this period was due to the money many had available to them. An unusually large number of Wynn Schwartz’s women were American heiresses and some were members of the European aristocracy, though often, like La Duchesse, Elisabeth de Gramont, they were also class traitors (“as noble in blood as they come but hardy as a wildflower, and a communist to boot”). Others, like Wilde’s niece, Dolly, were relatively poor and made an art of living off their friends. But to create the precious spaces (the salons, the stages, the islands villas) where women could breathe freely, required not only ingenuity but hard cash. Unlike the young heiresses in Edith Wharton’s The Bucaneers (1938) who came to Europe in the late 1880s only to tie themselves down to the fag end of the English aristocracy, these daughters of American industrialists and business barons, on inheriting vast fortunes, understood that money gave them the freedom to run their own lives. And this is what they set about doing: challenging themselves to consider what their existences had been and might yet become, and testing the extent of the liberty they had been accorded. Very few of them attempted to follow in their father’s footsteps and build business empires, instead they sought to dream up alternate versions of themselves through art; others found a different kind of reverie in their pursuit of women, alcohol or drugs.

For many the first sign of defiance was in the renunciation of the name they inherited, adopting instead one of their own devising. Then they took to nature (“out the back window and into the pine tree to read poems from a century less muffled in fabric”), draping themselves sensually over some hanging bough, at ease to think with a book in hand or to contemplate the vast blue sky. This was a trial version of living like the Greeks, out in the open rather than shut in as so many women had been cloistered throughout history. It was, after all, in the name of the “natural order” that women had been held back and kept indoors, but what exactly is “natural” many began to ask, as they undid their corsets and took to wearing trousers. From these acts of self-conjuring, and having opened themselves up to the sensuous pleasures of the physical world, they were better equipped to follow their dreams, for each woman to think about building an “island of her own invention”.

One way to announce the changes they were making was to write a manifesto, letting the world know what was on your mind, and inciting in others the demand for change. Another was to embark on a portrait of the newly-fashioned women in whose company you now resided in Paris or on some Greek island. Romaine Brooks’s muted and stripped-back paintings declared the boldness with which many had reinvented themselves, and the seriousness of their enterprise, with none displaying the collusive charm of traditional female portraiture (“Amazons not nymphs, Romaine said brusquely”). In literature, too, it was necessary to find new forms to express new selves (“some acts can only be written as fragments”). Woolf’s Orlando was so radical it made “no recourse to a category at all” – a lesson learned by Wynn Schwartz who, in After Sappho, has triumphantly devised her own free-floating form that glides through collective history while presenting, just as Brooks had, sharp vignettes of individual lives.

Unlike the portraits of many lesbians in literature, Wynn Schwartz avoids the damnation inflicted upon them in narratives that end, ineluctably, in bitterness, recrimination or death. Radyclffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928) is, of course, the template for many such stories and Wynn Schwartz rightly categorises the novel as a kind of wrong turn or dead end. Her novel, by contrast is partisan, often celebratory, and frequently characterised by surges of hope. But this does not mean it is sentimental in its portraiture. She does not shy away from the fact that some women put themselves on the wrong side of history, siding with the enemy in debates about empire and war. Perhaps the most egregious of these examples were those who succumbed to the fantasy of fascist modernity. The majority of women, of course, were horrified by “the virile hour”, seeing in its ultra-masculine culture the antithesis of everything they had being trying to give birth to.

Why Lina?

After Sappho draws to a close with a chapter called “Afterwords” which follows the last days of molten-eyed Lina Poletti as she fights against the virile hour, writes countless manifestoes and broadcasts to her compatriots, proclaiming “We are the chorus…the voice of us shall never be silenced”. Poletti was one of those Italian activists, name changers (“Cordula sounded like a heap of rope, Lina was a swift sleek line”), lovers and poets. But she was often misunderstood by her sisters. Even after we’ve written her, Wynn Schwartz avers, she still seems elusive and beyond our comprehension. In other words, Lina is like Sappho, and the thousands of other women lost in history that we must recover, because they can take us to novel states, “beyond ourselves”. The act of searching, studying and rediscovering goes on. La lotta – et l’amore – continuano.

Gayl Jones, The Birdcatcher, Virago – TLS

Catherine is in paradise, or Ibiza, which is a pretty good stand-in. Her life is adorned with palm trees and sunsets, and she is in possession of a beach house, successful art career, caring husband, and a good friend, Amanda, who often stays with the couple. Yet, for some reason, Catherine keeps trying to kill her husband. From this startling premiss Gayl Jones weaves a novel that is part mystery, part thriller and wholly captivating.

These three black Americans live a bohemian existence at the edge of Europe: Catherine works on a sculpture called The Birdcatcher, her husband, Ernest, writes about popular science, and Amanda makes her living as a travel writer. They spend their evenings wandering the old town and walking on the beach. But despite the beautiful scenery, Catherine’s violent outbursts and repeated incarceration in psychiatric institutions, suggest that, for her at least, paradise is a prison.

The Birdcatcher is narrated in the first person by Amanda, and it is through her watchful eyes that we encounter this loving but lethal relationship. The compelling oddness of the situation is compounded by the fact that everyone carries on as normal. Ernest tells Amanda about an article he is writing on psychokinesis and a woman who causes destruction as the “only way of expressing her little dissatisfactions.” But when Amanda asks if this might apply to his wife, Ernest replies, “I’ve stopped trying to explain Catherine”. The conspiracy of silence is not confined to Catherine’s behaviour: she accuses Amanda of covering her own life in secrecy. Gradually, The Birdcatcher’s enigmatic present opens out to Amanda’s past, making the reader privy to stories she keeps from Catherine – about her travels in Brazil, and the complex ways in which racism and sexism have stymied her relationships and discouraged her writing ambitions. After Catherine and Amanda visit a white friend, Gillette, the novel’s central question takes shape: what must a woman sacrifice to become a great artist? Gillette has a strangely unboundaried relationship with her daughter, who devours anything put in front of her. While the women watch the girl eat, Gillette uses poisonous mushrooms to create wild, unfettered canvasses, and pronounces: “Never kill your work for a man or a child, kill them first”.

Having begun her career to considerable acclaim in the 1970s, Gayl Jones fell from view before resurfacing when Beacon Press in America began publishing new fiction from her in 1998. The writer’s difficult life led to a rocky publishing history. Her champion and editor, Toni Morrison, dropped her from Random House because she disapproved of Jones’s relationship with her husband, a man Morrison thought unstable and abusive. The couple ran away to Europe to escape a warrant for his arrest, but shortly after returning to America a stand-off with the police resulted in his suicide. In Britain, Virago are now presenting The Birdcatcher as a “new novel”, though it appeared first in German translation as Die Vogelfaengerin in 1986. Jones is an outstanding writer and with The Birdcatcher’s emergence in English, alongside revived publications of her whole oeuvre, a vital part of the American literary canon has at last been restored.

Given her history it’s unsurprising that Jones shuns the limelight. It’s not just that her dramatic life-story has taken the focus from her work, it’s that her highly literary novels have sometimes been read through the lens of supposition about her life. A 2021 New Yorker review by Hilton Als argued that Jones’s subservience to her husband deformed her fiction. Earlier in her career June Jordan said that Jones’s portraits of black women reinforced degrading stereotypes.

Perhaps it is in part because of these kinds of criticism that Amanda’s narration in The Birdcatcher is dialogic; she addresses her readers in a way that acknowledges the arguments she might face from them (“feminist friends would be disappointed…”), or the subconscious errors that all authors make (“I started to write…”). Similarly, ideas that deny black literary tradition are incorporated in the novel (Gillette tells Catherine that black people have no “really great literature…so you really can’t use any great literary allusions in your work”) only to be belied by Jones’s artful and allusive fiction which makes reference to many black authors. Yet The Birdcatcher never succumbs to didacticism: much of its fascination lies in how expertly Jones allows meaning to surface, leaving the reader to decode the intention behind Catherine’s murderous behaviour, the possibility that Gillette has in fact poisoned her child, or that among Amanda’s secrets are a daughter she has abandoned. The girl is called Panda, and like one of Amanda’s lovers whose black skin has turned half-white, the name suggests that while not everything in life is simply black and white, however far to paradise you may run, racism and the structures of oppression cannot be transcended.

There’s a portrait of an author in The White Family (2002) – Maggie Gee’s novel about racism, written in the wake of the Stephen Lawrence murder – which is surely meant as a rebuke to the complacency of British fiction at the time. Thomas has written a minor novel and is now working on a “phony” book about postmodernism and the “death of meaning”. The irony of this is that he is embroiled in a story whose ample meanings pass unnoticed by him, just as they were overlooked by most British fiction then produced by white writers. The uncommoness of Gee’s tale is something Bernadine Evaristo notes in her Introduction to Telegram Books’ new edition of The White Family: “A rare white voice exploring race as a British novelist”.

Caught up in his books, Thomas doesn’t get out much, but when an attractive young teacher moves into a neighbouring flat, he finds himself agreeing to talk to a class of her students about his work. Wondering what it is that writers do exactly, he tries out a few clichéd phrases: “Writers don’t know where their stories come from. They come like magic, in the middle of the night”; then “writing is a way of bringing people together”, before coming up with an explanation that he thinks will seize the kids’ imaginations: “I’ll tell them, writers are time-travellers. Sending messages from six thousand years ago.”

Telegram Books have also just published Maggie Gee’s latest novel, The Red Children, and though set a few decades in the future, the messages Gee sends in it arrive from even further back in time than Thomas had estimated. They come in the form of a small band of naked children, washed up on the seafront in Ramsgate. For the people of Kent, Gee reminds us, this is not a particularly unusual sight as they have been used to migrants turning up on their beaches as far back as Julius Caesar’s landing. And just up the coast sits a large boat presented in commemoration of the Vikings’ arrival. More recently, climate change has brought refugees in smaller boasts, while viruses have seen people fleeing from the city’s “hot, germy cages” to Britain’s seaside towns.

But there are crucial differences with these new arrivals: the children’s red skin, prominent foreheads, indecipherable language, constant laughter, and the way they cling to one another, are all strange, and to some in Ramsgate, disconcerting. Are they quite human, a few residents wonder? Predictably, the more scaremongering reactions are whipped up by the town’s nationalist group, “Put Britain First”. Despite this, the good sense of the school’s headmaster prevails. The noisy, gangly children are welcomed into the town, proving against the expectations of many, to be mathematical geniuses who quickly pick up English and develop a fascination for history. When more red people arrive – one of whom, known as the Professor, is particularly erudite – it becomes apparent that the oddness of the newcomers stems from the fact that they are Neanderthals, driven by climate warming from the caves where they’ve been hiding in Gibraltar, just as 40,000 years ago their ancestors were driven south by climate cooling.

Written twenty years apart, the two novels are companion pieces in the stories they tell about xenophobia, and both analyse how failure and disappointment propel those characters drawn farthest into bigotry. The White Family is essentially a tragedy in its unflinching depiction of how prejudice deforms all aspects of life, while The Red Children, despite its discussion of ecological destruction and species extinction, is more resilient, veering into comedy. This in part mirrors the times when the books were written, reflecting small advances in our understanding of racism and willingness to confront it. Minor characters from the earlier work reappear in the later, now older and with greater authority – so Winston, a child in The White Family, develops into the head teacher in The Red Children who proves instrumental in encouraging the town to welcome and incorporate the newcomers. The unlikely optimism of The Red Children may also derive from the stage it was written in Gee’s career: this is her seventeenth book and the playfulness of the red children, and their intense curiosity, are infectious, leading some of the more curmudgeonly townspeople to act, despite themselves, with generosity or even heroism. This enjoyment of life spreads out across the town and throughout Gee’s narrative in a way that is often a feature of late-stage work, together with gratitude for the planet’s beauty, and a profound sense that we are all connected: Bob Marley’s ‘One love’ is a constant refrain.

Perhaps the greatest difference between the two novels, however, is in their treatment of what we might call ‘common ground’. The patriarch of The White Family is a park-keeper. His pride in the park and other communal spaces (many of which were fostered in the postwar years by the welfare state) give his family a sense of belonging: “We liked it here. It was our – El Dorado. Once upon a time, it had all we needed.” The tragedy of The White Family is that as Britain changes and new kinds of people enter the park, hospital, church or shop, the Whites, steeped in myths of empire and racial superiority, feel threatened and diminished. The message that the red children bring, by contrast, is that new understandings of history and science, shorn of supremacist assumptions, can help set us free: there is no need to feel threatened by outsiders as we have always interbred with newcomers, and this newness has made us resilient. If fear was the terrible motivator for the White family, what the red children bring, for all their differences, is awareness of our “likeness” – “in five or six generations, who will know the difference, or notice?”

“Make it big!”, is how Sophie Lewis, the English translator of Poetics of Work, recently explained her choice of title for Noémi Lefebvre’s slim fourth novel, aware that the modesty of its offering (coming in at just 112 pages), might lead to this brilliant, witty, utterly contemporary novel being overlooked or underestimated. This is precisely the fate of its ungendered narrator, who spends the book in a Socratic battle with their father, mostly about the disciplinary uses of work, but also about the absence of poetry in modern life, the racism of France’s increasingly militarized state (“Are we at war?” is a constant refrain), and the totalitarian power of western democracies in the twenty-first century. This power comes together, here, in the figure of the father-as-myth, a tyrannical daddy who embodies not only the state’s neoliberalism, patriarchy and colonialism but also its liberal critiques, making his authority of such a magnitude as to seem unassailable, and inculcating in his child a deep sense of futility. Finding him everywhere and doing everything, the narrator at first finds themselves nowhere, fitting into none of what Lefebvre calls “the categories that civilised humanity expects”.

The first of these controlling categories is gender. Although it is hard to read Poetics of Work without assuming Lefebvre’s narrator is female (the way the father dismisses and humiliates them particularly makes it seems so), no indication of this is given in the novel. Such elusiveness is just one of many ways in which the narrator fights back, allowing them to speak as the voice of a generation that has found itself locked out of employment and housing, questioning the values of a society that no longer works for it: “who is this we, Papa”? Liberally educated, and pursuing, idiosyncratically, ideas that help them to understand the strange new world they inhabit (reading Klemperer for his analysis of fascism, and Kafka for his understanding of father-fear and the difficulty of dissent, as well as internet memes and pieces of pop culture), our narrator chips away at the father’s granite logic and sense of entitlement, as if knocking a statue from its pedestal. Slowly his monolithic qualities are unmasked as a fraud: Papa hasn’t actually read many of the thinkers that he uses to bolster his oblique yet emphatic pronouncements. And the child knows the father better than his public image: for much of the time he is either mysteriously absent or feasting on junk food while watching daytime soaps in his underpants.

Through the process of questioning and unpicking the logic of authority something starts to shift. The narrator finds “solidarity” and agency in city crowds as “someone among everyone…loiterers against the law”, and we sense that, finally, we are approaching the autumn of the patriarch, or maybe even their final winter.

This review appeared in the TLS as ‘Knocking a Statue’ on 13.8.2021.

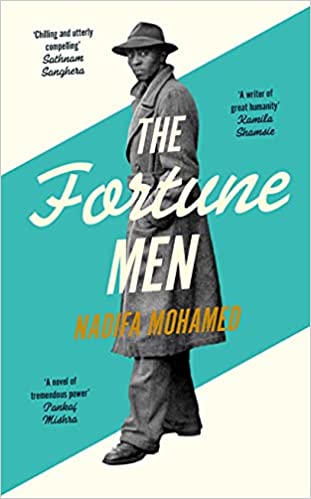

While it may appear that British fiction is now an encompassing, multicultural affair, Nadifa Mohamed’s novels challenge this idea, rendering physical and psychological landscapes that are largely absent from the canon of a country yet to come to terms with its colonial past. Her previous books were set in Yemen in the 1930s and Somalia in the 1980s. Her latest, The Fortune Men, takes us to a multiracial community in 1950s Wales. Once again Mohamed is intent on expanding her world, listing its teeming varieties and presenting a wealth of character and language: Somali, Welsh, Arabic, Yiddish, Hindi and German all jostle together on her pages. But this proliferation contrasts with the constricted minds of many people in postwar Britain.

The Fortune Men is predicated on the real life of Mahmood Mattan, a Somali man who was hanged for murdering a Jewish woman in Cardiff in 1952. Mattan always maintained his innocence and decades later, after a long campaign by his family, the conviction was finally quashed. In Mohamed’s novel – as he was in life – Mattan is nicknamed “the ghost”, without fixed work or address he haunts the fringes of society. But Mattan is also a globally connected figure: speaking five languages he is more worldly than the people who dismiss him as an illiterate alien. It is this tension between the perception of Mattan as a shadowy figure, someone who can be easily fitted up for murder, and his struggle to make sense of his wide-ranging life which fires up The Fortune Men, illuminating something the wandering Somali half-grasps: he is ahead of his time, a passenger on “the ship of a world to come”.

As a writer, Mohamed shares with her protagonist the loneliness of the pioneer, which is perhaps why she tips her hat to a handful of novels which have lit the path to this “world to come”. (Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet, 1999, Bernadine Evaristo’s Mr Loverman, 2003. and Andrea Levy’s Small Island, 2004, all make incidental appearances). What distinguishes The Fortune Men from these earlier works about immigrant experience is the level of (controlled) rage on display. Perhaps this can be attributed to the fact that although seventy years separate the story and its telling, Mohamed’s descriptions of racist violence are still shamefully relevant. Perhaps it is a mark of the growing confidence of a new generation of black writers at work in Britain, among whom Mohamed is one of the outstanding figures. Or it may have to do with the fact that this is the first of Mohamed’s novels to be set in the heart of the empire.

The Fortune Men begins as the new queen takes to the throne, a change of regime that will have little impact on Mattan, a sailor who has abandoned the ocean for life as a gambler, roué, and petty thief in the cosmopolitan enclave of Tiger Bay. Mattan has walked the length of Africa and sailed on every sea but he is held now in this Welsh port by his love for a local girl and their three sons, though their marriage is bedevilled by prejudice, fear, and Mattan’s inability to settle down. A few streets away Diana, a war widow, and her sister Violet, close up the shop they keep. Violet’s brutal murder traps Mattan in a fate he struggles to comprehend. “The police are all liars”, he thinks and, once accused, his strategy is to dissemble and invent, a tactic that has served him well in a life of wriggling free from the hands of his mother, his brothers, bosses and lovers, from anyone who would pin him down.

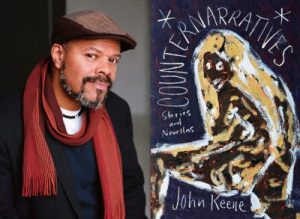

Many writers are now thinking about how to represent racism without reinscribing its justification or depriving its victims of agency. One answer, deployed by John Keene in Counternarratives (2015), is to uncover the irrationality of prejudice, allowing characters to escape its logic. Another, used by Colson Whitehead in The Underground Railroad (2016), is to introduce fantasy into historical events. But in fidelity to the facts of Mattan’s life, Mohamed does not grant herself the leeway of creative circumvention. In releasing their characters from historical facts, the American writers break out of the realist form. Mohamed, by contrast, stays within its confines, revealing the intractability of the system which betrayed Mattan, and his cognitive dissonance in the face of its injustice. It is Mattan’s own lawyer who seals his fate. He recognizes his client’s evasiveness but is incapable of interpreting it as a strategic manoeuvre, characterising him as a childish liar and “semi-civilized savage” (here Mohamed quotes from the court record).

Terrifyingly, the novel’s final act of imaginative outwitting belongs not to the victim but the perpetrator. The British state performs a kind of conjuring trick revealing that Mattan’s cell was never a place from which release was possible or justice could be obtained: hidden behind a piece of furniture in the cell, an execution chamber was hiding all along. Two warders “heave the wardrobe aside to reveal an entrance to another room. A noose hangs from the ceiling. The familiar cell swims around him and his mind cannot make sense of it.”

In the early 1980s, I read Andrea Dworkin’s Pornography: Men Possessing Women. Many of the young women I knew at the time were reading the book and it was part of the reason they were turning to radical feminism. Dworkin’s representation of an epidemic of trans-generational male violence against women shook me to the core. I remember in particular her descriptions of household utensils used in sadistic acts made me uneasy at the sight of everyday objects such as kitchen knives and glass bottles. In Everybody: A Book About Freedom, Olivia Laing revisits Dworkin’s polemic and recalls a similar experience she had reading Pornography the following decade, how its “terrifying and incantatory” words transformed the library where she sat into something “sinister”. Dworkin’s intent was to find a form of words that would wake women up to what she considered an ongoing genocide. A difficult task not least because, as Jacqueline Rose observes in On Violence and On Violence Against Women, there are “obstacles that litter the path between sexual violation and language.” Perhaps chief among these is the fact that sexual violence has so often been cloaked in silence, the crimes largely unreported, the victims, ignored or pilloried if ever they tried to speak – a fact which makes the powerful eloquence of these two new books even more remarkable.

In Everybody, Laing quotes Rose’s words on language (taking them from a 2016 essay subsequently reworked into Rose’s book). Though these works are related, their writers have set themselves different tasks: Rose questions why violence seems more ever-present and visible, Laing investigates the body’s powers and pleasures, as well as its discontents. They have different styles, too – Rose’s is more oratorial, Laing’s more personal – and sometimes their attitudes diverge: for instance, from the outset Rose proclaims her opposition to Dworkin’s idea of an immutable masculinity, while Laing gives Dworkin’s thesis its full context and due, before she dissents from portions of the argument.

But there is plenty of common ground between these books, which goes beyond their feminism. Both are radically subversive and yet impressively learned works that address violence at an individual and state level, reminding us that despite neo-liberalism’s privatisation of our bodies and emotions, the personal is still political. Both swim in the stream of this perilous moment – of would-be totalitarian leaders, BLM, #MeToo, Covid and climate change – progressing broadly from discussions of sex to race. Both look to thinkers, artists and activists for examples of how to respond to oppression while imagining the world otherwise, how to embody and “manifest a freedom that is shared”, as Laing puts it. And both are threaded through with the lives and ideas of psychoanalytic pioneers: in Rose’s case the connecting figure is Sigmund Freud; in Laing’s, it is Freud’s pupil, Wilhelm Reich.

As Laing reports, it was over the question of “body language” that Reich first began to part company with his mentor. He came to believe that the talking cure was not enough: perhaps the past isn’t just buried in the memory but stored in the body, too, a burden that by touching their patients, therapists could alleviate. Although this was forbidden in psychoanalysis, Reich went ahead anyway and found his patients achieved a release of blocked energy which he called “streaming” or “orgone”. Laing tracks Reich through the 1930s in Berlin, when, full of optimism, he coined the phrases “sexual politics” and “the sexual revolution”, up to his painful split from Freud. The older man felt Reich’s theory about magical orgasmic energy was wild enough, but his membership of the Communist party and refusal to submit to Nazi demands for the Aryanisation of psychoanalysis, caused the final rupture between them.

At first Laing reads Reich alongside Christopher Isherwood. Both were involved with Magnus Hirschfeld’s ground-breaking Institute of Sexual Research, finding liberation in Berlin’s cabarets and underworlds before escaping from what Isherwood memorably called “Hitler’s weather”, when the streets were “scarlet with swastikas”. Once Reich is exiled from fascism in America, she winds the maverick’s life through the Beatnik world of Ginsberg and Burroughs, who popularised his invention of the notorious Orgone Box, an energy “accumulator” in which the patient could be sexually and spiritually recharged. She goes on to find echoes of Reich’s intellectual struggles – liberation in a box? – in feminist artists who reacted to restrictive gender norms by creating art concerned with freedom and confinement, pointing to the work of Ana Mendieta “where the body was many things at once…always in flux”, and Agnes Martin, who painted grids, nets and little boxes composed of dots or dashes where “there is nothing to hang onto…inducing a kind of rapture in the viewer”.

A consideration of the de Sade’s years in the Bastille leads Laing to explore imprisonment by the state, and in one’s own body, including discussion of the contesting responses Dworkin and Angela Carter made to the Marquis – the former uncovering the actual harm and pain suffered by de Sade’s servants and prosititues, the latter viewing the transgressiveness of de Sade’s writing as metaphorical and didactic, suggesting that “there might be something useful to discover in the interminable prison cells of his imagination”. Then Laing analyses the impact of incarceration on the neglected black gay activist Bayard Rustin and on Malcolm X, throwing up interesting correspondences between Malcolm X’s critique of “the global trans-historical system of white supremacy, the grotesque forced domination of one kind of body over another”, and Dworkin’s of male supremacy. She ends with a eulogy to the woman who sang “I wish I knew how it would feel to be free”, the ultimate liberation artist, Nina Simone.

As in her earlier books The Trip to Echo Spring (2013) and The Lonely City (2016), Laing displays a talent for parallel biography (including elements of her own), and for uncovering the myriad ways that art is always an act of resistance. Like Christina Stead, she is not a writer who romanticises the margins, recognising the risk of becoming wayward to the point of meaninglessly weird, or succumbing, as Reich did in the Fifties, to a climate of paranoia and violence. In Laing’s judicious and moving account, we come to understand how the man who called for free female sexuality turned into a wifebeater, how someone who “longed to help people unlock the prison of their bodies, ended up locked in a prison cell himself.”

If Laing’s project is to rehabilitate Reich and present him as emblematic – traduced and cast out from the mainstream but vindicated by the impact his prescient ideas had on later activists – Rose’s reading of Freud, an ongoing project for her, re-presents this canonical figure as continuingly relevant and more subversive than many have understood. “For a woman”, Rose argues in one of two chapters on sexual harassment, “Freud comes close to saying that normality in and of itself is an injury from which no girl will ever recover…it is a type of invasion.” While in an essay on recent political protest in South Africa, Freud’s attention to “hidden histories” casts light on what happens when liberation movements carry around “an additional psychic burden”. In this case, their relationship to a previous wave of activists, to whom they owe a debt, but whose project of emancipation has stalled, descending into corruption.

In both books there are productive tensions: Rose argues with radical feminists (Dworkin’s collaborator Catharine MacKinnon comes in for repeated knocks), while Laing does battle with Susan Sontag, particularly her (punitive and contradictory) ideas that illness is without meaning – or that it’s meaning derives from a lack of willpower. And inevitably there are unresolved paradoxes: Rose’s essays are titled after Hannah Arendt’s work On Violence (1970), to which she adds and On Violence Against Women, explaining her augmentation of the subject. Acknowledging Arendt’s influence, she redeploys the philosopher’s view of power as thoughtless, and of violence as stemming from a vengeful “impotence of bigness”. But Dworkin herself expressed similar opinions, arguing that “The immutable self of the male boils down to utterly unselfconscious parasitism”, and “He is always in a panic, never large enough”. To some extent, I think that the arguments between radical, socialist and liberal feminism which characterised the women’s movement in the Seventies and Eighties, have today collapsed. This, in part, is because women of colour, seeing the limitations of each of these schools, demanded a more inclusive, intersectional approach which now shapes the way many feminists think; and in part it’s because, unexpectedly, some arguments seem to have crossed over, as is the case of those socialist feminists who argue an essentialist line against transgender women.

Rose dedicates two essays to thoughtful dissections of recent debates about what trans means – including the fear of some cis women that they are being erased or marginalized, or the argument that only post-op are people ‘properly’ trans – before insisting that “For me, trans women have earned their place at the banquet of feminism”. For Laing, the genesis of her book was the feeling of never having been at home in her own body, and she now embraces a trans identity while married to a man and keeping her female name and pronouns. This widens the possibilities of trans, which some critics regard only as an extension of the dreaded sexual binary. In Everybody, Laing notes that Hirschfeld found in his study of sexuality there are “forty-three million possible combinations of gender and sexuality”, adding, gleefully: “Imagine telling J.K. Rowling”.

At the end of On Violence, trying to answer her own question about about the proliferation of violence against women Rose argues that we will not conquer the problem without facing up to it. We must acknowledge the human frailty that the “bloated masculinity” of autocrats and domestic abusers seeks to deny. This is not so far from and Laing’s opening observation that “our bodies carry our unacknowledged history, all the things we try to ignore or disavow”. Both writers show what a long way we still have to go to free ourselves from violence, stigma and shame, but their books bring us closer to understanding the task and the prize. As Laing writes, “The free body: what a beautiful idea!”

This review first appeared in the TLS on 11.6.2021 as ‘Stored in the Body’.

Anna North, Outlawed. Bloomsbury – TLS

We may think that witches are a thing of the past but only last month Mary Beard admitted that the term was still hurled at her on Twitter, just as it has been used for centuries as an insult against women beyond child-bearing age. Plagues too, were something most of us, in the West at least, had thought consigned to history. But as 2020 reminded us, the past has a way of erupting into the present. Understanding this, in her new novel, Anna North plays similar tricks with ideas of progress and time. A reimagined Western set at the end of the nineteenth century, Outlawed begins in the aftermath of a pandemic that has weakened fertility and left ‘barren’ women vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft.

North’s inquisitive protagonist, Ada, is the daughter of a midwife who battles against the patriarchal religion flourishing in the pandemic’s wake. Soon, the teenage girl becomes a wife who is unable to conceive, and as the month’s pass with no sign of pregnancy, the town’s latest pariah. Her life in danger, Ada is bundled off to a nunnery for safe-keeping. She escapes from this cloistered space, however, preferring adventure with a team of cross-dressing bandits. But even as Ada succumbs to the romance of outlawry, living wild and learning how to survive in the bitterest of winters, the question spurring her on concerns the biological mystery that led to her banishment: why do so many women have trouble with conception?

North has a lot of fun taking liberties with history: the group Ada joins are a female version of the Hole in the Wall gang, all exiles and misfits from the punitive mainstream, for reasons of sexuality, race or insubordination. Their charismatic (in today’s parlance, non-binary) leader is the “Kid”, and Ada is renamed “Doc” because of her medicinal skills. These narrative freedoms are mirrored in the gang’s ungoverned behaviour: when Ada first encounters them they are dancing, singing, drinking and kissing under the moonlight. But such freedoms are hard-won, reliant, North emphasises on expertise – in horses, food, firearms and fooling people: one member teaches the others how to dress like flighty women or to bind their breasts and walk like macho men, conning the unsuspecting in the execution of Kid’s elaborate hold-ups.

Kid is absent from the novel’s final scam, holed away from the rest of the gang with a debilitating depression. This at first seems jarringly anachronistic, the concern about mental illness of a piece with Outlawed’s highly contemporary views of identity. But with great intelligence, North manages to weave these current preoccupations into a historical narrative, asking her readers to reconceive how gender might operate, but also how we might build community, democracy and leadership to effect political change.

This review first appeared in the TLS on 28.5.2021.

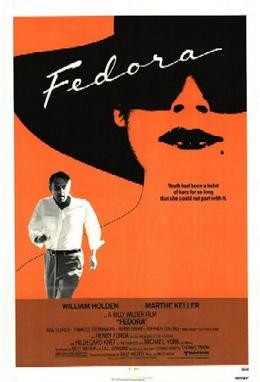

Jonathan Coe, Mr Wilder & Me. Viking – TLS

“Flawed and bonkers, but I like it” is how Jonathan Coe once described Fedora, the penultimate Billy Wilder film at the heart of his thirteenth novel, Mr Wilder & Me – an assessment that catches the manner of much of his own work. As Stanley Kramer’s 1963 movie declared, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, and among contemporary British writers, Coe has been one of the readiest to see that art needs something of the unhinged to adequately encompass life. In his novels, ‘normal’ people are often besieged by forces of derangement and excess, forces so powerful they sometimes beget supernatural beings: there are monsters in the cellar in his 2015 novel, Number 11. Coe’s engagement with cinema helps him manoeuvre between these different realms or realities – an imaginative response to a divisive British class system. His best-known work, a satire on rampant Thatcherite privatisation, was named after the Pat Jackson 1961 film What a Carve Up!. But it is Billy Wilder – an Austrian-born, Polish-Jewish Hollywood director – who has been Coe’s guiding light as a writer, leading him to claim the director as his “first literary influence”.

Coe’s longstanding obsession with Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes might seem a more obvious subject for him to explore, but Fedora is the film that best conveys Wilder’s coupling of the mad and the melancholy, a mix which also infuses Coe’s writing. In Wilder’s film, an aging Hollywood star, the eponymous Fedora, subjects her daughter to plastic surgery so she can impersonate her mother on screen, sustaining the myth of her undying beauty. As Coe notes, Wilder forbade his writing partner, Iz Diamond, from adding jokes to their script because he wanted to create a wholly serious work. This means the demented behaviour, so liberating in their previous films, here manifests itself in catastrophe: in Fedora, impersonation results in a lethal loss of self, and the movie’s camp quality derives not from cross-dressing or wisecracking, but its elegiac mood.

The film’s melancholy also infects Coe’s novel, making it more subdued than some of his earlier fiction, particularly in its examination of late style. The narration by a fictional character, Calista, begins in London and looks back to her first encounter with Wilder and Diamond some forty years earlier in Los Angeles, followed by her employment as their translator during the shoot for Fedora in Greece, Munich and Paris. Mr Wilder & Me is divided into chapters named after each of these places, and Calista’s wistful memories are matched by Wilder’s own nostalgia, as he is prompted by each new location to reminisce about different moments in his life.

Alongside this narrative retrospection, Coe reflects on the demise of Wilder’s viability as a director, the “invisibility” of women like Fedora once they lose their looks, the end of classical Hollywood, and even of cinema itself. There is something terminal, too, in his characters’ judgement that British culture is not European. For the Polish Diamond, for instance, “England is not Europe”, while Calista notes that her Greek family “found many [British] customs and mores to be occult, eccentric and indeed incomprehensible”.

Although narrated in 2020, much of Coe’s book is set in the 1970s. The Wilder that Coe gives us is painfully aware that his Mitteleuropean light comedy, with its touches of elegance and ennui, is now seen as old-fashioned compared with the mean streets and dangerous spectacles offered by Scorsese, Spielberg and Coppola – the “kids with beards”, as Billy and Iz call them. By this point, the two Europeans responsible for such quintessentially American films as Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Some Like It Hot (1959) are struggling to finance Fedora. The ascendancy of a younger generation means that Hollywood’s once revered stars have become fallen idols, kicked out of paradise. Trying to obtain finance from German bankers, and keep up with the vogue for violence, the older men joke about branding their film, “Jaws in Venice”.

The foil for Coe’s tale of fallen gods and goddesses is Calista, the modest “& Me” of the title. She is another of Coe’s ‘normal’ people, pitched against beings of another order. This time, however, these are not reactionary and destructive; they are creators, and Calista is grateful to be admitted to what remains of their “heaven”, a cultured world very different from her own prosaic one. The ingénue – an obvious stand-in for younger readers, unfamiliar with cinema history – is schooled by Wilder in the delights of French wine and cheese, but her greatest lesson concerns her mentor’s part in the story of Central European writers, directors, musicians and artists exiled by fascism to Hollywood. Deepening his novel’s homage, Coe has Calista write a script about Wilder’s period at UFA, Germany’s principal film studio, where he worked alongside Robert Siodmak, Fred Zinnerman, Emeric Pressburger and many other Jews who were all sacked in 1933, but defied the anti-Semites by going on to create archetypal American movies, or, in Pressburger’s case, in partnership with Michael Powell, the greatest British films of the postwar period.

Coe has fun, too, with many of the transatlantic ironies this culture-crossing produced, notably Wilder’s exasperation when Al Pacino, the boyfriend of Fedora’s German star, insists on ordering cheeseburgers even in Europe’s finest restaurants. Beneath Wilder’s unspoken irritation – why can’t Americans adapt to Europe the way Europeans adapted to America? – there is a larger point, Having lived through the horrors of war and fascism, and, like Pressburger, having lost family in the camps, Wilder chose by and large to make sardonic comedies. In other words, the violence that the “kids with beards” are so attached to seems unearned, the product of a settled existence. A director, Wilder contends, should give their audience “something elegant, a little bit beautiful … You don’t need to go to the movies to learn that life is ugly.”

By the end of his novel Coe, with an elegant touch of his own, brings together Calista’s and Wilder’s worlds with the use of one word. Calista is inspired by Wilder’s “fundamentally generous impulse” to create Fedora in the teeth of disregard, and she decides that her family must also find the “impulse…will and energy” to solve their domestic problem. These impulses to give to one another, whether in everyday acts of kindness or in acts of transcendent creativity, are not so different, Coe suggests. In this way, he collapses his habitual divisions, reuniting mortals with the gods of art.

This review appeared in the TLS on 6.11.2020 titled ‘A Fedora Tip to Beauty’.

With the third volume of her trilogy about the life of an “ordinary” African woman, Tsitsi Dangarembga has completed one of the most penetrating accounts we have of the continent’s difficult, often violent, transition from colonization to globalization. Since 1950 millions of people have fought to emancipate themselves from European rule, only to find that the nations which emerged from this struggle were not always the ones they had hoped for, and the work of liberation must go on.

Part of the power of Dangarembga’s account comes from the angle at which she approaches this history. Unlike many novels about Africa’s turbulent decolonization, in This Mournable Body, the central character, Tambu, is unremarkable. Brought up in Rhodesia in rural poverty, now as an adult in the 1990s, eking out a living in Zimbabwe’s capital, she is neither a freedom fighter like her sister and aunt, nor an activist like her cousin, nor even, in any straight-forward manner, a victim. And yet the circumstances of her early life – a childhood in the 1960s during the war of independence (described in Nervous Conditions, 1988) in which a brother was killed, her sister, maimed; teenage years in a convent (The Book of Not, 2006) where “closeness to [the racism of] white people…ruined your heart” – have damaged Tambu’s capacity for empathy, and bred in her an all-consuming need for self-preservation. When we encounter her in This Mournable Body, Tambu’s determination to succeed, coupled with the constant thwarting of this ambition (white colleagues appropriate her work, her age and sex discount her), have left her an intriguingly complex and perverse figure.

In the first two novels of her trilogy, Dangarembga introduced the young Tambu in a bright first-person narrative which drew the reader in. In this third volume, where we find the weary adult Tambu “labouring to define the beginning of her fading”, the author has chosen a second-person narrator who sounds at times like Tambu’s taunting, internal voice, at others, a condemnatory universal force. This tactic allows Dangarembga to fully exploit the second-person’s accusatory form: a “you” that singles out Tambu, emphasising her egotism and isolation, as well as her feelings of persecution. “You cannot afford definite conclusions for certainty convicts you”, the narrator upbraids her when she is unsure if she has broken another rule at the hostel where she lodges. Tambu’s materialist fantasies can make her envious and cruel (she joins a mob attack on a glamorous woman from the hostel), and cause her to block out her past where “nothing ever glittered and sparkled”. But the energy of her discontent also propels Tambu forward into new situations in which, incapable of masking her resentment, she fails repeatedly. Unable to find “prestigious” work, Tambu returns to teaching but sabotages her advancement with a frenzied attack on a pupil, enraged by the confidence her young charges display. A voice inside her head tells her the pupils are not a threat and need only guidance, but this is dismissed. Desperate to outshine others, she “fights…against the perils of contemplation”, deluding herself about what she has done.

Tambu’s self-deception mirrors that which Teju Cole describes in his 2015 essay, ‘Mournable Bodies’, after which Dangarembga named her novel. “Moments of grief”, Cole wrote, following the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo, do not “absolve us of the responsibility of making distinctions”. The west’s “ahistorical fantasies” overlook its atrocities, making it difficult for many to understand why they are being attacked. In Unmournable Bodies, Tambu is equally incapable of frank self-assessment and therefore bedevilled by a past she cannot reckon with or take responsibility for. When Tambu’s mother sends her a bag of “mealie meal”, she hides it away, feeling the corn porridge mocks her desire for advancement and rebukes her for neglecting parents living in near-starvation. Made mad by this situation, she lands up in a mental hospital only to be rescued by her cousin, Nyasha, who has recently returned from Europe married to a white man. Inexplicably to Tambu, even with these “advantages”, Nyasha chooses to live at the margins, teaching young women to analyse their lives through storytelling.

Finally, a chance encounter with a white acquaintance leads Tambu to a job in one of Zimbabwe’s few booming businesses: eco-tourism. She works hard following orders, but when her boss asks her to give an opinion, she cannot. In a subtle and intelligent novel that dissects Zimbabwe’s political malaise through the crisis of one woman’s personality, this is one of Dangarembga’s most interesting arguments. Unlike many of her contemporaries Tambu has not been tortured, yet her awareness of how her country men and women have acted under conditions of war and starvation mean that she is paralysed by fear. Knowing the brutal penalties meted out to those who offend, or even stand out, she is incapable of original thought. The imagination, Dangarembga seems to suggest, is not an inviolable attribute to which we have recourse whatever the circumstances: to flourish it requires the freedom from retribution neither Tambu, nor many other “ordinary” citizens in Zimbabwe enjoy.

Irene Sabatini’s Act of Defiance is set after Dangarembga’s story, addressing events in Zimbabwe during the last two decades. Sabatini’s protagonist, Gabrielle, is also an ordinary woman, but as a middle-class lawyer in Harare, she escapes her country’s descent into lawlessness, fleeing to Colombia and Italy. Growing up, her status as “Coloured” made her a target of cruelty. Now, an adult, she is slow to realise “The Old Man” – as Gabrielle refers to Robert Mugabe – is becoming increasing malign. Once nicknamed Vasco de Gama (someone opening routes between west and east), far from creating a more tolerant country, he and his marauding ex-soldiers turn Zimbabwe into a pariah state, terrorizing all opposition. Gabrielle and her client, Danika, the child victim of a sexual predator in the “Party”, are kidnapped from a courthouse in the capital, then raped and tortured in one of the “interrogation” camps overseen by a leader who emancipated his people, but now tyrannizes them.

Sabatini’s story unfolds in alternating chapters which juxtapose sunny scenes of Gabrielle’s love affair with an African-American diplomat, and the nightmare conditions at the camp where a boy in the Youth Army “re-educates” his hostages by screaming twisted revolutionary slogans: “Down with imperialist saboteurs!…Down with economic prostitutes!…Down with gay gangsters!” As the American writer, John Keene noted in his story ‘Lions’ (2015), the situation in a country like Zimbabwe is all the more horrific for its degeneration from liberation to barbarity, and for the way in which the language of enlightenment is perverted into an instrument of subjugation.

Dangarembga and Sabatini have written compelling novels about brutal experiences: both feature the hyena as a metaphor for derangement (every laugh in This Mournable Body feigns, mocks or threatens); and both contain what Dangarembga has spoken of as the “location of hope” – something that sustains humanity and possibility in circumstances where they face erasure. For Sabatini, the act of defiance which snaps Gabrielle out of her “fear-fuelled inertia” is the creation of a centre in her Harare home to help people like Danika; for Dangarembga, it is Nyasha’s storytelling project run from her garden – modest, improvised projects which might pass under the radar of power. In a trilogy which has foregone consolation, however, perhaps Dangarembga’s most significant assertion of the possibility of hope, is Tambu’s liberation from her histrionic selfishness, as she works, finally, to pay her debt to Zimbabwe’s unmourned bodies.

This review appeared in the TLS on 19.6.2020 titled ‘Ahistorical Fantasies’.

There is an interview with the movie critic David Thomson in which he tells a story about being at film school, picking up other students’ off-cuts from the editing suite floor and splicing them together. When he shows the finished work to his classmates, he experiences a revelation. Instead of laughing off the series of random images, as he expects, they sit around discussing the meaning of what they’ve seen. Whatever you do to disrupt chronology, Thomson realizes, the mind will always try to make connections between the disparate, to find sense in sequence and to construct a narrative.